Seeing Plants as Living Beings

Imagine walking through a forest, not just noticing trees as “green cover,” but sensing them as living beings—beings with moods, strengths, and vulnerabilities, almost like people. To the ancients of India, plants weren’t scenery. They were kin. The neem wasn’t just “a medicinal tree”; it was a patient with ailments and a healer with remedies. The mango wasn’t just “fruit-bearing”; it was a provider, a family member whose well-being mattered. This worldview—plants as conscious participants in life—laid the foundation for what later became known as Vriksha Ayurveda, the science of plant life. And unlike modern textbooks that separate ecology, spirituality, and agriculture, ancient India wove them seamlessly together

The Rigveda: Plants as Voices of the Divine

The Rigveda (c. 1500–1200 BCE) is often seen as hymns to fire and cosmic order, but tucked inside are surprisingly intimate references to plants.

Soma: The Immortal Elixir

The Soma plant was called the “king of plants.” Its juice, extracted and offered into the sacred fire, symbolized vitality and immortality.

“We have drunk Soma and become immortal; we have attained the light, the gods discovered.”

Rigveda 8.48.3

Think of it this way: today coffee or tea gets us through the morning. Imagine if coffee was also considered a gateway to higher consciousness. That’s the spiritual weight Soma carried—both stimulant and sacred.

The Oshadhi Sukta: Hymn to the Healing Herbs

The Oshadhi Sukta (Rigveda 10.97) is a hymn of 63 verses where herbs are invoked as divine mothers. Each plant is called upon for healing, whether it came from mountains, rivers, or forests.

“The herbs that sprang up from the waters, from the mountains, and from the heights of the earth—I call upon them for healing. May they free us from distress.”

Rigveda 10.97.1–3

What’s striking is the intimacy here. The seers didn’t just “use” herbs; they spoke to them, prayed to them, and treated them as active agents in healing. Compare that with today’s model: we swallow a pill with little thought for the chemicals it’s made of. For the ancients, healing was a relationship between human, plant, and divine.

Atharvaveda: Plants as Protectors and Physicians

If the Rigveda was poetry, the Atharvaveda (c. 1200–1000 BCE) was practical spirituality. It dealt with everyday life—health, farming, pest control, prosperity.

“Let this plant bring us children, cattle, and food. May it destroy the worms that feed on the crop.”

Atharvaveda 2.8.2

Farmers didn’t just attack pests—they invoked the plant’s own ability to defend itself. This is closer to today’s integrated pest management than chemical pesticides.

“May the plants protect us from disease, may they guard us from decline, may they guard us from untimely death.”

Atharvaveda 5.17.4

Healing wasn’t just physical. The same turmeric used for wounds or neem for infections was invoked with mantras. The chant set intention, the herb provided medicine. In modern language, this was mind-body medicine at work long before we coined the term.

Plants were described as sentient. Some were “angry” if misused, others “happy” when worshipped. This concept—plants having temperaments—may have seeded the later dosha theory in Vriksha Ayurveda, where plants, like humans, were understood to have constitutions and vulnerabilities.

Upanishads: The Philosophy of Plant Life

The Upanishads built on this worldview, placing plants at the very heart of existence.

Food as Prana

“From food arises being; from food arises strength; from food arises prana (life-force); from food arises faith, truth, and all existence.”

Chandogya Upanishad 6.5.4

Food comes from plants. Plants capture sunlight, store it, and release oxygen. In other words: we live on the breath and energy of plants. For the sages, this wasn’t a metaphor—it was the foundation of life itself.

Plants and Human Identity

Taittiriya Upanishad 3.2:

Describes the five sheaths (koshas) of the self: body, prana, mind, knowledge, bliss. The first sheath, Annamaya kosha, is the food sheath—literally our body formed from plants. Without plants, there is no body, no breath, no mind.

The Cosmic Tree

“The tree is one, but it has many branches. The truth is one, sages call it by many names.”

Rigveda 1.164.20

This image later reappears in the Bhagavad Gita (Ashvattha tree, Chapter 15), where roots are in the divine, branches in the world, and fruits as human experiences. The metaphor was clear: nature is interconnected. Harm one branch, and the whole tree feels it.

Beyond Ritual: The Deeper Wisdom of Vriksha Ayurveda

Planting Trees as a Sacred Duty

Imagine someone telling you that planting a single tree could give you the spiritual credit of raising a thousand children. Sounds exaggerated, right? But that’s exactly what the Padma Purana says about planting a peepal tree (Ficus religiosa). Another verse goes further: plant a mango tree, and you’ve basically reserved yourself a seat in heaven.

At first glance, these might sound like religious exaggerations meant to inspire people. But behind the symbolism lies an ecological brilliance: tree planting as a sacred act guaranteed mass afforestation.

Why these specific trees?

Peepal (Ficus religiosa): One of the rare trees that produces oxygen not just in the day but also at night. Beyond that, it is a biodiversity magnet, offering habitat for birds, bats, insects, and epiphytes. Spiritually, it was tied to Lord Vishnu, and the Buddha attained enlightenment beneath one — making it both ecologically vital and culturally sacred.

Neem (Azadirachta indica): Called “the village pharmacy,” neem’s antifungal, antibacterial, and insecticidal properties made it a natural pesticide long before chemicals existed. It purified air, soil, and even the human bloodstream when used medicinally. In effect, neem trees were guardians of both people and crops.

Mango (Mangifera indica): Mango wasn’t just a fruit. It was shade, wood, food, and a cultural icon. Mango leaves still adorn homes during weddings and festivals as symbols of fertility and prosperity. By making mango planting an act of religious merit, society ensured these highly useful trees flourished everywhere.

By linking tree planting to punya (spiritual merit), people didn’t need to be convinced through policy or fines. Religion and culture did the work of conservation naturally.

Reference: Haberman, D. L. (2013). People Trees: Worship of Trees in Northern India.

Arthashastra’s Agroforestry

From religion, we move to politics. The Arthashastra, written by Chanakya (Kautilya) around the 3rd century BCE, is often remembered for its ruthless advice on espionage and statecraft. But dig deeper, and you find entire sections on ecology and agriculture — showing how central farming was to governance.

“The Superintendent of Agriculture shall sow seeds according to the season… Trees useful to humans shall be planted on roadsides, in royal gardens, and forests.”

Arthashastra, Book II, Chapter 24

- Tree-lined Roads: Officials were ordered to plant useful trees — mango, coconut, medicinal species — along roadsides. This wasn’t only about aesthetics. Travelers got shade, food, and medicine on their journeys. Roads became lifelines of survival, not just trade routes.

- Orchards and Irrigation: The state supervised orchards and irrigation systems. Farming wasn’t left entirely to individuals; it was treated as a matter of collective prosperity. A kingdom’s wealth depended on healthy crops, and the king’s officials were accountable for it.

- Policy-driven Sustainability: Planting wasn’t charity; it was law. In today’s terms, agroforestry was “mainstreamed” into government policy. Compare that with modern times, where most tree planting happens through temporary campaigns.

What we reinvent today was law 2,000 years ago. To neglect agriculture was to neglect the state itself.

Reference: Rangarajan, L. N. (1992). Kautilya: The Arthashastra.

Varāhamihira’s Brihat Samhita: When Stars Guide Seeds

By the 6th century CE, knowledge had evolved into vast compilations like the Brihat Samhita by Varāhamihira, an astronomer, mathematician, and polymath. This massive text, spanning astrology, architecture, botany, and agriculture, is one of the clearest examples of how holistic thinking shaped ancient Indian science.

Astrology in Agriculture

Varāhamihira prescribed planting, grafting, and harvesting according to planetary alignments, lunar phases, and constellations. To modern eyes, this might sound like superstition — but compare it with biodynamic farming in Europe, which still aligns sowing and harvesting with lunar cycles. The idea was simple: time human activity to nature’s rhythms, not against them.

Architecture in Villages

The Brihat Samhita also connected vaastu shastra (science of architecture/dwellings) to agriculture. Village layouts, water tanks, groves, and fields were designed to maximize harmony between people and the environment. This is eerily close to today’s “eco-villages” and permaculture principles, where settlement design integrates food, water, and shelter seamlessly.

Agricultural Innovations

Varāhamihira also described advanced horticultural practices:

- Seed treatments to boost fertility and germination.

- Grafting methods to combine strengths of different plants.

- Inducing off-season flowering and fruiting, essentially early plant biotechnology.

This was holistic science—stars, soil, and settlements seen as one interconnected system.

Reference: Sastri, T. Ganapati. (Ed.). (1904). Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira.

Rituals as Ecology in Action

When we look at the Vedas, we often see “rituals” — yajnas, offerings, sacred groves. But step back, and you notice they were ecological strategies encoded as spirituality.

Yajnas (Fire Rituals)

“May Agni carry our offerings to the heavens and return to us rain.“

Rigveda 1.68.4

Grains, ghee, and herbs were offered into fire. The belief was that this nourished the gods, who would send rain in return. Scientifically, yajnas release volatile compounds into the air — some with antimicrobial and pest-repelling qualities. In villages, this was like an ecological fumigation ritual.

Reference: Pandey, D. N. (2000). Sacred rituals and ecological balance. Current Science, 79(3).

Sacred Groves (Devavanam)

“The forest is the mother of rivers, and the abode of plants and gods.”

Atharvaveda 5.30

Forest patches dedicated to gods were off-limits for cutting or grazing. These became biodiversity hotspots. Even today, India has over 13,000 sacred groves.

Mawphlang Sacred Grove (Meghalaya): Protected for centuries by Khasi tribes. Entering requires permission, and nothing can be taken—not even a leaf. The grove harbors orchids, rare fungi, and unique fauna.

Sarpa Kavu (Kerala): Sacred snake groves around shrines. These preserve groundwater recharge zones and shelter medicinal plants. Families still maintain them as part of ancestral duty.

Pachmarhi Groves (Madhya Pradesh): Tribal communities guard these groves, rich in medicinal species. Knowledge of herbs here passes orally from generation to generation.

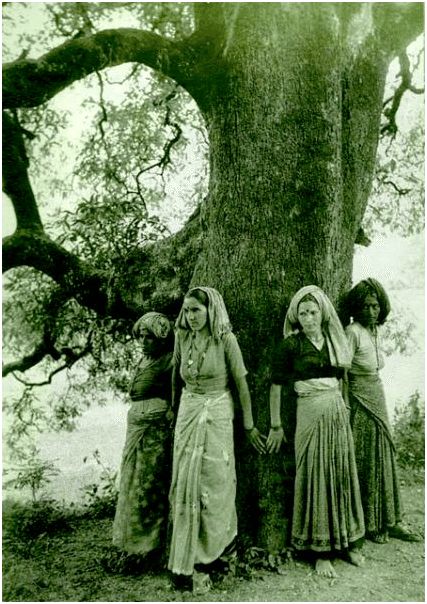

Khejarli (Rajasthan) – Where 363 Bishnois sacrificed their lives in 1730 CE to protect khejri trees.Reference: Gadgil, M. & Vartak, V. D. (1976). Sacred groves of India. JBNHS.

Tree-Planting Merit

Linking spiritual rewards to trees like peepal, neem, and mango ensured people planted them everywhere. Religion was the driver, ecology the outcome.

This was systems thinking disguised as devotion. What looked like faith was often science in action.

Why This Matters Today

What seems like “ritual” or “myth” was actually systems thinking at its best. Spirituality ensured ecology. Policy ensured farming. Astrology ensured timing.

- Sacred groves = protected biodiversity zones.

- Yajnas = ecological purification and pest management.

- Tree-planting rituals = large-scale afforestation campaigns.

- Arthashastra = policy-based agroforestry and irrigation.

- Brihat Samhita = agricultural calendars, eco-architecture, and horticultural science.

In modern times, we’ve fragmented these into separate fields: permaculture, regenerative agriculture, forest gardening, ecological architecture. The ancients wove them together into a single worldview where spirituality, ecology, and survival were inseparable.

Maybe the future doesn’t need brand-new solutions. Maybe it needs us to remember the old ones, dust them off, and apply them again.

That’s the deeper wisdom of Vriksha Ayurveda—not just about plants, but about how to live in rhythm with them.

If this article sparked your curiosity, here are some carefully chosen books on Vriksha Ayurveda, Ayurveda, and the ecological wisdom of ancient India. They’ll help you connect the dots between tradition and practice — and even bring some of these timeless ideas into your own life. Click on the books that interest you to get your copy on Amazon.

Core Texts on Vriksha Ayurveda & Traditional Agroecology

- Vrikshayurveda Samhita (Principles of Agro Ayurveda)by Ravi Singh Choudhary

A comprehensive guide to the ancient science of plant care, this book covers topics like soil types, irrigation methods, and plant diseases, offering practical insights for sustainable agriculture. - VrikshAyurveda : Ancient Indian Tradition of Sustainable Agriculture by PG KRISHNA KUMAR

This work explores the integration of traditional practices with modern agriculture, emphasizing eco-friendly farming techniques and the restoration of soil health. - Brhat Samhita of Varahamihira (2 Volumes) by M. Ramakrishna Bhat

A 6th-century Sanskrit encyclopedia that covers a wide range of topics, including agriculture, astrology, and architecture, reflecting the holistic approach of ancient Indian science. - Vrikshayurveda – Traditional Agro Techniques for Ashwagandha by Dr. Yogita Patil Dr. Priya Mohite,Dr. Sonesh Utkar

This concise 61-page guide delves into the ancient Indian science of plant life, focusing on sustainable cultivation practices for Ashwagandha. It covers aspects such as soil selection, planting techniques, irrigation methods, and pest management, all rooted in traditional Ayurvedic principles.

Ayurveda & Ecological Wisdom

- Ayurveda : Life, Health and Longevity by R. E. Svoboda

An accessible introduction to Ayurveda, this book delves into the principles of health, healing, and longevity, offering insights into the holistic approach of ancient Indian medicine. - The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India Part – II [Formulations] – Volume – I, II, III and IV (Set of 4 Books) [Hardcover] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare – the govt of India

A government publication detailing standardized formulations in Ayurveda, providing a scientific basis for traditional remedies. - Sacred Plants of India by Nanditha Krishna, M. Amirthalingam

This book explores the cultural and ecological significance of India’s flora, highlighting the deep-rooted connection between plants and spirituality.

Cultural Perspectives & Spiritual Insights

- People Trees: Worship of Trees in Northern India by David L. Haberman

An exploration of the religious and cultural significance of tree worship in northern India, shedding light on the sacred relationship between humans and trees. - Sacred Groves in India by Kailash C. Malhotra

A detailed study of India’s sacred groves, these ecologically rich areas serve as a testament to the traditional conservation practices and spiritual reverence for nature. - Sacred Groves and Local Gods: Religion and Environmentalism in South India by Eliza F. Kent

This book examines the intersection of religion and ecology in South India, focusing on the role of sacred groves in environmental conservation. - Religion and Ecology in India and Southeast Asia by David L Gosling

A comparative study of religious and ecological practices in India and Southeast Asia, highlighting the role of religion in environmental stewardship.

Foundational Texts for Broader Context

- The Arthashastra by Kautilya

An ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy, offering insights into the governance and societal organization of the time. - Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate by Peter Wohlleben, Pradip Krishen

A modern exploration of the complex life of trees, drawing parallels between scientific findings and traditional wisdom. - Sacred: THE MYSTICISM, SCIENCE, RECIPES & RITUALS around the plants we worship by Vasudha Rai

A contemporary look at the spiritual and practical aspects of plant worship, blending science with tradition.

References used for this article

Padma Purana (various dates, c. 4th–15th century CE). Verses on tree planting and merit.

Gadgil, M. & Vartak, V. D. (1976). Sacred groves of India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society.

Haberman, D. L. (2013). People Trees: Worship of Trees in Northern India. Oxford University Press.

Pandey, D. N. (2000). Sacred rituals and ecological balance. Current Science, 79(3), 275–285.

Rangarajan, L. N. (1992). Kautilya: The Arthashastra. Penguin Books India.

Sastri, T. Ganapati (Ed.). (1904). Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira. Government Press, Trivandrum.

Primary Sources:

Rigveda (c. 1500–1200 BCE). Hymns including Oshadhi Sukta (10.97).

Atharvaveda (c. 1200–1000 BCE). Selected hymns on plants and protection.

Chandogya Upanishad (c. 800–600 BCE). Chapter 6, Section 5.

Taittiriya Upanishad (c. 600 BCE). Book 3, Annamaya Kosha.

One response

[…] parts of this series, we met plants the way the ancients did—as living beings, and as guides in sustainable farming. But the story of Vriksha Ayurveda doesn’t end with rituals or farmers tending rice paddies. It […]