In the first two parts of this series, we met plants the way the ancients did—as living beings, and as guides in sustainable farming. But the story of Vriksha Ayurveda doesn’t end with rituals or farmers tending rice paddies. It also lives in the ink of old palm-leaf manuscripts, where philosophers, doctors, priests, and even empire-builders codified their plant wisdom into enduring texts.

What they left us isn’t just knowledge—it’s an inheritance.

In this part, we’ll walk through the Samhitas, the Puranas, the Arthashastra, and finally, Surapala’s Vrikshayurveda. Each is a chapter in humanity’s love story with trees, each written in a different voice—clinical, poetic, political, and devotional. Together, they remind us that our survival has always been rooted in green.

The Samhitas

When exploring the Samhitas, look for two key aspects: timing and provenance rules, and preservation and pharmaceutics.

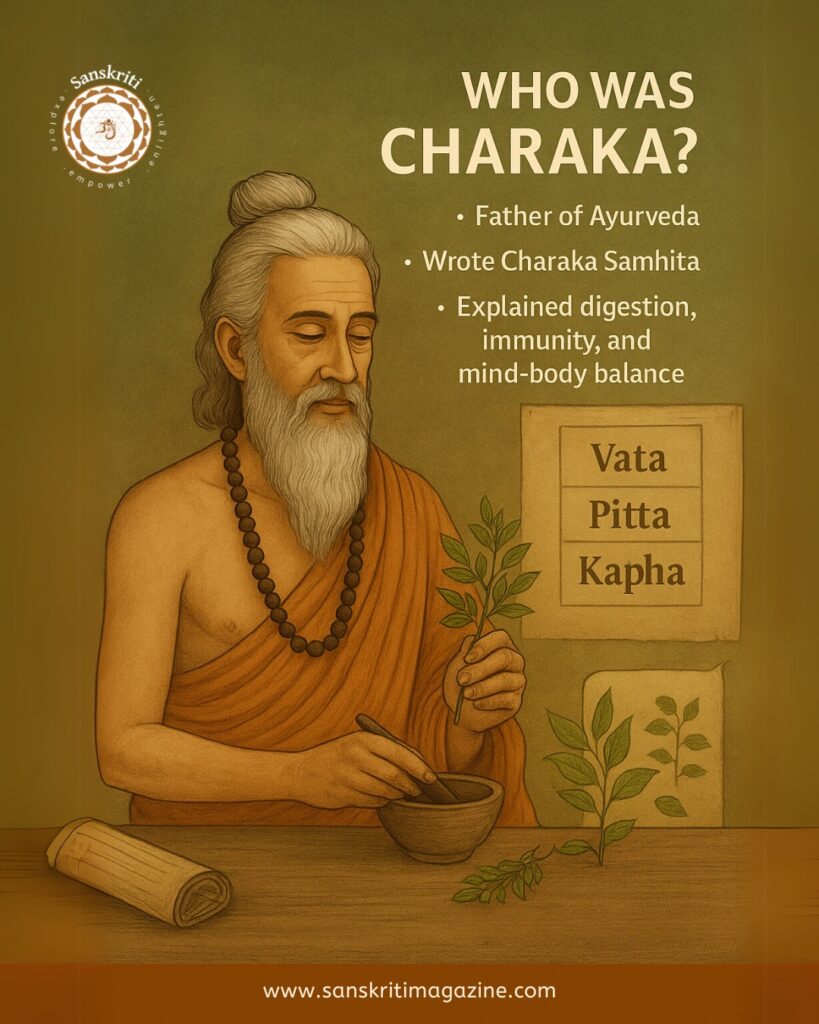

Charaka Samhita (1st–2nd century CE) was one where plants were analyzed with surgical precision. He grouped herbs by taste (rasa), potency (virya), and their effects after digestion (vipaka)—a framework that farmers could just as easily apply to soil enrichment as doctors did to healing (Sharma & Dash, Charaka Samhita).

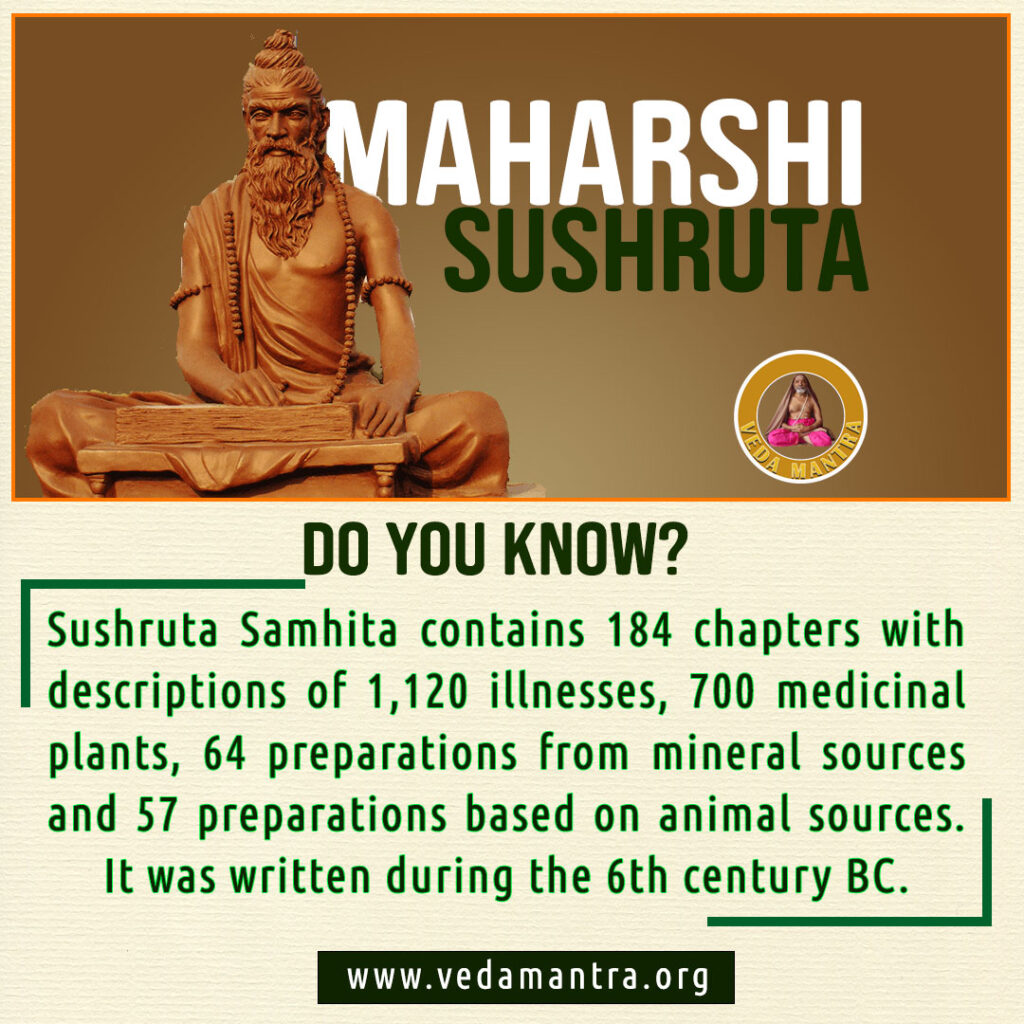

Sushruta Samhita (3rd–4th century CE) emphasized sourcing. His instructions for gathering herbs sound uncannily like modern sustainability guidelines: harvest in the right season, offer respect to the plant before cutting, never strip a root system bare (Bhishagratna, Sushruta Samhita).

Both texts saw a continuum: the health of the body was linked to the health of the forest.

Picture this: A village healer waits until dawn on a spring morning. The moon is waning, the air is crisp, and he heads out barefoot to gather bark from a particular tree. Not just any bark, and not just any day. Charaka and Sushruta had written centuries earlier that plants harvested under certain seasons, even under particular stars, carry their full potency. The healer doesn’t see this as superstition. He knows from experience — bark cut at the wrong time loses its strength, fruit gathered too late turns heavy and sluggish in its effect. To him, timing is medicine.

This is where the Ayurvedic Samhitas first teach us: plants are not passive. They’re alive, with rhythms of their own, and the way we meet them — time, place, season — shapes their gift to us.

Timing & Preservation

Charaka says a fruit that has matured in the right season is medicine; the same fruit, if immature or overripe, can cause imbalance.

Sushruta points out that roots harvested in the rainy season absorb excess moisture — they tend to lose concentration of active compounds, spoil quickly, and may even develop fungal contamination. Roots dug in the dry summer, on the other hand, are denser, more fibrous, and store longer — but may be harsher in action.

Think of turmeric: freshly dug during monsoon can rot in storage, while turmeric harvested in summer is drier, easier to cure, and stronger in its medicinal effect.

Or consider ginger — monsoon ginger tastes watery and pungency is weak, but dry-season ginger carries the fiery kick Ayurveda values for digestion.

For preservation, the Samhitas instruct:

- Shade-dry herbs instead of sun-drying, to prevent volatile oils from evaporating.

- Store in glazed or oiled jars to keep pests and damp away.

- Fumigate storage rooms with herbs like guggulu or neem leaves — an ancient pest-control method.

Agni Purana: Where Planting Becomes Prayer

A few centuries later, The Agni Purana – one of the great encyclopaedic texts of the Puranic age, adds another layer: the act of planting itself becomes ritual.

There’s an entire chapter on vṛkṣa-pratiṣṭhā — the proper way to “establish” a tree. It tells you which stars are auspicious for planting, where to position thorny trees (south of houses, as natural boundaries), and how to design groves.

Auspicious nakshatras (stars) such as Rohini and Mrigashira are said to ensure healthy establishment of trees.

Thorny trees (like babul or karanja) should be planted on the south side of houses, to act as windbreaks and natural guards.

Shady fruit trees like mango or jackfruit should be placed in courtyards where families gather — food and shade in one.

Sacred groves should mix flowering and fruiting species, so that both humans and birds are fed.

If you plant shade trees on the south or west, you’ll reduce summer heat in your house — an ecological design hidden in a “ritual” rule.

Laws didn’t reach every village, but stories and rituals did. If cutting a tree became taboo, entire groves survived. That’s how sacred groves — from Kerala’s kavus to Rajasthan’s orans — held biodiversity long after the forests around them vanished. Even today, walk into a sacred grove and you’ll feel the air change: thicker, quieter, alive with species you won’t find in the fields outside.

The Agni Purana was clever. It encoded practical ecology (plant this tree here, don’t plant that tree there) inside cultural sanctions (cutting trees equals sin). Modern conservationists still struggle with enforcement. Maybe the Purana got it right: people obey stories more than fines.

The Arthashastra: Chanakya’s Green Economics

Kautilya or Chanakya, the political strategist who engineered the Mauryan Empire (4th century BCE). His Arthashastra isn’t poetry. It’s a manual for running a state. And yet, ecology is everywhere in it.

His dravyavanas — forests specialized for mango, sandalwood, or bamboo — read like the earliest forestry departments. Superintendents oversaw them, fines protected them, and even processing factories were tied to them.

But beyond what we already know — the plantations, the penalties — something subtler stands out: the Arthashastra treats the seed itself as policy. It instructs rulers to secure the best seeds, prepare them with washes or treatments, and align sowing with rainfall cycles.

To Kautilya, bad seed wasn’t just a farmer’s problem — it was an economic risk for the state.

That detail resonates today. Governments still run seed certification schemes, subsidize improved varieties, and guard against seed hoarding. The Arthashastra shows that this logic — control the seed, control the harvest, control the treasury — is ancient.

Kautilya understood what modern governments often forget: forests are economics.

- He appointed Vanapalas (forest protectors) and Sitadhyakshas (superintendents of agriculture) to manage green wealth.

- He set fines for cutting down useful trees and rewards for planting orchards.

- He ordered trees planted along highways, both for shade and for trade benefits (Kangle, The Arthashastra).

One section even details irrigation networks so crops wouldn’t fail in drought. That’s climate resilience, 2,300 years before the term existed.

“For a leader, he should consider not just human beings but also plants, animals, water body and the mineral world as his citizens. He should take care of all.”

Chanakya

Surapala’s Vrikshayurveda: The Gardener’s Bible

By the 10th century CE, plant wisdom had matured into its own standalone science. Surapala, a court scholar under King Bhimapala, composed the Vrikshayurveda—a text devoted entirely to trees and their care (Vrikshayurveda of Surapala, edited by Venkatasubramanya Sastri, 1946).

Core techniques from Surapala

1) Kunapajala — the fermented, animal-based liquid manure

The recipe, in Surapala and later compilers, commonly reads: collect animal remains/excreta (boar, other horned animals, fish etc.), boil with water, store in an oiled pot with husk; add oilcake (sesame), honey, soaked black gram and a bit of ghee, then incubate in a warm place for two weeks. The resulting liquid — kunapajala — is applied diluted to roots or sprayed. Surapala and later writers claim strong growth and flowering responses. (Internet Archive)

Modern tests show kunapajala and similar fermented organic inputs (Pancha-gavya variants, vegetable ferments) contain usable nutrients and bioactive compounds and can act as growth promoters and pest modulators — though sanitation, standardized dosing, and cultural acceptability are practical concerns. The recent nutrient analyses and field trials show measurable benefits but also underline the need for standardized prep for safe, scalable use. (PMC)

Practical, modern-friendly kunapajala

If you’re curious but squeamish, there are plant-positive alternatives inspired by the same logic (fermentation to make nutrients bioavailable): vegetable ferments (sasyagavya), fish emulsion (for non-vegetarians), or controlled on-farm compost teas. If you do experiment with animal-based ferments, follow food-safety-style hygiene (covered vessels, controlled fermentation, proper dilution, no direct use on edible parts close to harvest).

Surapala’s flexibility in ingredients is actually an advantage: it allowed farmers to use locally available waste. (Internet Archive)

2) Seed selection & pre-sowing treatment

Surapala emphasizes:

- Collect seeds from healthy, well-fruited trees (phenology matters).

- Clean and then treat seeds: soak in water, sometimes in herbal decoctions or cow urine mixtures, dry/store by season — to improve vigor and storage life.

- Field prep: ploughing and leveling, intercropping small pulses and sesame as green manuring/cover during initial planting cycles. (PMC)

Why it’s clever: pre-soaking + herbal decoctions are early priming — they soften seed coats, wash away inhibitors, and sometimes inoculate beneficial microbes. That’s low-tech seed priming. Modern seed priming literature echoes these advantages (salts, hormones, microbial inoculants) — ancient farmers found functional equivalents. (PMC)

3) Pits and soil-preps

- Surapala prescribes pit shapes, mixing soil layers with char/ash, bones, oilcake, and manure — essentially early biochar + compost + mineral amendments.

- He details spacing rules for fruit trees (distance for canopy and root spread), orientation advice for wind and sunlight, and mulching concepts. These are classic horticultural rules made local and precise. (PMC)

4) Grafting and cut-treatment protocols

Surapala and other classical horticultural manuals describe propagation by grafting, budding, and stem propagation.

Cuts are to be protected: smear with mixtures such as honey + ghee (fat + antimicrobial sugar) and then covered with cow-dung or mud to seal (these were wound dressings).

Similar wound dressings appear in the Arthashastra’s agricultural chapters too. These are adhesives, sealants, and antiseptics in one. (studylib.net)

Modern note: honey does have antibacterial properties; fats and packing reduce desiccation. Today we use sterile wax or grafting tape — same idea, better standardization. If you’re experimenting with traditional methods for heritage gardens, the old smears can be instructive; for production orchards, stick to hygienic, proven grafting tapes and sealants. (Easy Ayurveda Hospital)

5) Watering, scratching, and topical treatments

Surapala prescribes specific responses to over/under-watering and various pests: scratching roots or stems and smearing with honey + certain herbal powders, smoking certain plants with specified materials, and targeted fumigations.

He classifies maladies as internal (dosha-like) or external (pests, weather), and offers both nutritional and topical treatments accordingly. (PMC)

Science Meets Spirit

What strikes me most in Surapala is not the recipes, but the rhythm. For every practical instruction — “soak this seed, smear that cut” — there’s a ritual one: “plant on this star, chant this mantra, offer water at dawn.” It’s tempting to dismiss the ritual as superstition. But that misses the point. Though many wouldn’t understand the science behind the ‘rituals’, it was the delivery system for the science.

Think about it: if farmers are told “prime your seeds,” maybe half will forget. But if they’re told “on the day of this star, soak seeds as an offering to the gods,” they’ll remember. Rituals create discipline. They enforce seasonality, protect trees, and keep communities aligned. The science ensures results. Together, they made practices durable — lasting not just for a season, but for centuries.

That’s the genius of Vṛikṣha Ayurveda. It wasn’t just botany, and it wasn’t just belief. It was the weaving of the two. And that weaving gave us forests that fed, groves that healed, and practices that survived the rise and fall of kingdoms.

Threads That Tie Them All

What unites the Samhitas, the Puranas, the Arthashastra, and Surapala?

- Plants as kin (Samhitas): Study them as you’d study a friend’s temperament.

- Plants as sacred (Puranas): Tie them to story, ritual, and emotion.

- Plants as economy (Arthashastra): Guard them as state treasure.

- Plants as destiny (Surapala): Planting them secures heaven itself.

Together, these weren’t “just” texts. They were an ecosystem of thought—bridging doctor, priest, ruler, and gardener.

Why This Still Speaks to Us

As climate anxiety grows and soil erodes under chemical farming, these voices aren’t relics. They’re reminders.

- From Charaka and Sushruta: harvest respectfully. Don’t take more than you need.

- From the Puranas: give cultural meaning to ecology—make tree planting sacred again.

- From Kautilya: legislate for forests as fiercely as for finance.

- From Surapala: blend science with ritual; let farming be both work and worship.

We don’t need to copy their methods word-for-word. But their mindset—seeing nature not as commodity, but as companion—is the medicine our fractured world craves.

A few Takeaways for the Modern Gardener

Here are a few simple echoes of Vṛikṣha Ayurveda you can try today:

- Harvest basil (tulsi) before flowering — keeps potency high for tea or remedies. (Charaka Samhita)

- Save seed from your healthiest plant, not just the first one that fruits — vigor is hereditary. (Surapala’s Vṛkṣāyurveda)

- Plant shade trees on the south or west side of your home to cut heat load — a Purāṇic tip with modern eco-benefits. (Agni Purana)

- Use ash or charcoal in soil mixes — Surapala recommended it, modern soil science confirms its biochar effect.

- Offer water to trees at dawn — not just a ritual: evaporation loss is lowest then, water uptake is best. (Surapala + modern horticulture)

- Protect fresh grafts with honey + beeswax if you don’t have grafting tape — honey is antimicrobial, the wax seals moisture. (Surapala’s method modernized).

Further Reading for the Curious

You don’t have to stop here. Some of the original texts and modern interpretations are available in book form — a chance to sit with the wisdom at your own pace, and maybe even try out a few practices in your garden or home. Below are some carefully chosen books you can find on Amazon India. Each one opens a different window into the world of ancient plant knowledge.

- Charaka Samhita 7 Vol set (English Translation, Sharma & Dash)

– A foundational Ayurvedic text detailing pharmacology, plant use, and seasonal rules of harvest. Perfect for readers who want to go deeper into the clinical side of Ayurveda that your article highlights. - Charaka Samhita (Translated into English)

– One of the foundational texts of Ayurveda, focusing on human health but with frequent references to plants, their timing of collection, and preservation. For anyone interested in how ancient doctors saw the relationship between plants and healing. - Sushruta Samhita (Bhishagratna’s English Translation)

– The classic surgical and botanical manual of Ayurveda, with sections on sourcing and preserving herbs. Great for those curious about Ayurveda’s roots in both medicine and plant science. - Arthashastra by Kautilya

– Kautilya’s Arthashastra is often remembered as a treatise on politics and economics, but it also contains detailed policies on agriculture, irrigation, forestry, and natural resource management. Think of it as an early state manual on how to protect and profit from trees — from specialized mango groves to sandalwood reserves. - VrikshAyurveda : Ancient Indian Tradition of Sustainable Agriculture by PG KRISHNA KUMAR

– This book delves deeply into the scope of this science. The wisdom of Vrikshayurveda offers a better option for the necessity of eco-friendly farming in today’s world. - Sacred Groves and Local Gods: Religion and Environmentalism in South India by Eliza F. Kent

– Drawing on fieldwork conducted in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu over seven years, Eliza F. Kent offers a compelling examination of the religious and social context in which sacred groves take on meaning for the villagers who maintain them, and shows how they have become objects of fascination and hope for Indian environmentalists. - Sacred Groves in India by Kailash C. Malhotra, Yogesh Gokhale & Sudipto Chatterjee

– The book covers various cultural and ecological dimensions of sacred groves in India, and describes recent initiatives undertaken by various stakeholders to strenghten this multifarious institution. - The Complete Book of Ayurvedic Home Remedies

– A user-friendly guide to everyday herbal remedies, which can help connect readers with the “medicine from plants”. - A Handbook of Ayurvedic Medicine

– A compact reference for herbal formulations, useful for readers who may want to apply ancient recipes in modern settings. - Black Yajurveda: Taittiriya Samhita

– One of the four Vedas, the Taittiriya Samhita includes rituals and hymns tied to agriculture, planting seasons, and the sanctity of trees. It gives cultural and spiritual context for why trees were always more than “resources.” - Samaveda Samhita (Translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith)

– Known as the “Veda of melodies,” Samaveda may not be a farming manual, but its chants were used in rituals for prosperity, rain, and harvest. It highlights how music, plants, and ritual life intertwined in Vedic society. - White Yajurveda: Vajasaneya Samhita

– Another Vedic text with sections on agricultural rites and the symbolic role of planting. It also contains mantras recited during sowing and harvesting — a reminder that even food production was seen as sacred. - Atharvaveda Samhita (Translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith)

– Sometimes called the “folk Veda,” it contains charms, spells, and practical references to plants for healing and protection. Its earthy, everyday tone makes it feel closer to the common people and their relationship with plants.

Resources & References Used In This Article

- Surapala’s Vrikshayurveda

Infinity Foundation: Surapala’s Vrikshayurveda – An Introduction - Vrikshayurveda: Ancient Science of Plant Life

WisdomLib – Vrikshayurveda and Environmental Philosophy - Indic Mandala: Surapala’s Vrikshayurveda

Indic Mandala Article - Modern Science on Vrikshayurveda Practices

PMC Article – Technology from Traditional Knowledge: Vrikshayurveda Expert System - Collection Practices of Medicinal Plants

ResearchGate Paper - Collection & Preservation of Ayurvedic Herbs

Easy Ayurveda – Article - Vrikshayurveda in Indian Culture

Culture & Heritage – Vrikshayurveda Article

No responses yet